Get Good at Delivering Software

This post was originally published on CIO.com on March 17th, 2021.

What if I told you that Blockbuster had a 7-year head start on streaming video over Netflix? What if I told you that before Prime Video, Prime Shipping, Google Docs, and Android phones, Amazon was a place to buy books and Google was just a search engine like Altavista. Altavista?

How were these companies able to enter new and existing spaces that had nothing to do with where they started and be successful? They were good at delivering software. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella says, “Every company is a software company.” If you buy a tractor from John Deere, one of the most important things that gets updated on that tractor is not the oil filter, it’s the software. There is a company with 3,500 engineers, 500 software releases a week, and 4,000 apps or services in production. That company is Home Depot.

If “software is eating the world,” as Marc Andreessen is famous for saying, and you want your company to do the eating, instead of being eaten like Borders Books, Barnes & Noble, and Blockbuster… then you need to get good at delivering software.

Situational awareness

The economic historian Carlota Perez, building on some definitions from Joseph Shumpeter, explains that we are currently in the 6th modern technological revolution. She argues that new paradigms replace old ones, which are marked by a “turning point” at which the new paradigm becomes fully dominant. The current revolution is the Age of Information and Computers, and if software is the new paradigm, this is a good explanation for the rise of companies like Netflix, Google, and Amazon. Being good at software enables them to enter and dominate spaces that were once controlled by others.

An Innosight report notes, “We’re entering a period of heightened volatility for leading companies across a range of industries, with the next ten years shaping up to be the most potentially turbulent in modern history.” This turbulence sounds very much in line with the ideas of Dr. Perez.

Being good at delivering software in this new age will be table stakes for any company that wishes to survive. According to the Dell Digital Transformation report in a survey of technology leaders, “Almost 1 in 3 are worried their organization may not survive the next couple of years.” Does your company have the systems it needs to be able to survive and thrive on the other side of the turning point?

Home Depot, a home improvement store, has made massive investments in technology for the past few years. According to Fortune, “new technology tools let store workers see a fuller picture of a shopper’s spending history and offering them insights for upselling. The company’s e-commerce operation grew more than 20% last year.” This means the pace of competition is actually accelerating. The Dell report showed that the Digital Adopters segment jumped by 16% between 2018 and 2020 compared to only 9% for the previous two-year period.

This fits in well with Dr. Perez’ thesis that mass production was the signature aspect of the previous technological revolution. Now we are in the age of software.

The question becomes: Is your business, are your investments, ready to compete in this accelerating age of competition, creative destruction, and innovation? Do they have the tools, the expertise, and the culture necessary to make it through the turning point, or will they be left behind?

It’s helpful to remember, as W. Edwards Deming said, “It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory”.

Implications

“It is not big beating the small anymore, instead it is fast beating the slow.” - Gene Kim

Gene Kim, author of The Phoenix Project, says it’s not about being a large, established player anymore. Speed is the strategic differentiator in this part of the curve. But why?

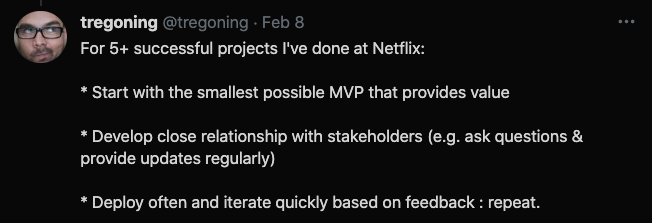

Eric Reis, in his book, The Lean Startup, describes the process for product development and finding product market fit as running a series of experiments. The goal being to “learn more quickly what works, and discard what doesn’t.” He advocates for what he calls MVPs, Minimum Viable Products. These aren’t the fastest things that can be developed that just barely work. They are carefully crafted learning experiments that allow one to determine if this is an idea worth pursuing or whether one should acknowledge a low-cost failure and move onto the next hypothesis. If a company takes six months to run an experiment, they will be a lot further behind in the fail-fast-and-succeed cycle than one that can run one or more experiments daily.

Think back to our Netflix vs. Blockbuster example. Netflix is good at delivering software. They release thousands of “experiments” every day. Blockbuster possibly had some large, slow, consulting company with antiquated development practices releasing experiments every few weeks or months. Who would have the competitive advantage in determining the best way to deliver streaming movies in that case?

One key is to maintain a strong customer focus in the design and product phases of development and work on a very short release cadence. Jez Humble, co-author of Continuous Delivery, explains: “One of the ways to blur the lines between design & delivery & shrink the overall value stream lead time is for teams to practice hypothesis-driven development & TDD, working in very short cycles to get code (including experiments) into prod (using an experiment framework).”

There is an even more compelling reason to get code into production as quickly as possible: inventory. Toyota Manufacturing worked with Dr. Deming (whom I quoted above) on process improvement in the 1970s and is famous for inventing just-in-time manufacturing. What problem was Toyota trying to solve with this invention? Inventory. Toyota realized that carrying excess inventory was expensive whether on the input or output side of the equation. In either case, they had to pay to store this inventory, which was wasteful and expensive. In addition, inventory was basically capital they had spent which they were unable to turn into revenue. If they had parts in a warehouse, they couldn’t make money on those parts. If they had cars sitting outside a factory, but people couldn’t buy those cars, they couldn’t make money on those either.

With software, it’s the same. If we pay our developers to write software, but that software is sitting in a code repository somewhere, that is an investment we’ve made in our business that we can’t make money on. If that’s the case, when do we make money? When the software is deployed in production. That’s when our customers can see value in what we’ve developed and increase their subscription or recommend it to colleagues. That’s also where we can run experiments to determine what will drive revenue or achieve product market fit. If there is a long delay between when the code is written and deployed, it’s just idle inventory. Capital invested without return.

Whither DevOps

So how do we solve this problem? How do we get good at delivering software?

I’ve been involved with the international DevOps movement for approximately the past decade. I’ve spoken at DevOps conferences, written a DevOps course, and been featured in some of the DevOps books. This is how I view DevOps:

DevOps is a Collaboration between Development, Operations, and other teams with the recognition that we are tasked with achieving common business goals.

The outcome of being good at DevOps is being good at delivering software. We know that the outcome for the entire business is increased business performance. How?

The 2019 Accelerate State of DevOps report and the companion book Accelerate determined that “highest performers are twice as likely to meet or exceed their organizational performance goals.” Consider this proposition if you haven’t already: becoming good at delivering software doubles your chances of meeting or exceeding goals for customer satisfaction, market share, revenue, etc.

What the researchers discovered was that there are four key indicators that predict company performance in the highest performers: Deployment frequency, lead time for changes, change failure rate, and time to recover. It is easy to see how these indicators fit in well with the idea of experiments as advocated in the Lean Startup and at Netflix. The first two indicators deal with how quickly and how often we can get our experiments into production to test a theory or a new way of doing things.

They are also a great measure of how quickly we can deploy security fixes. Which leads us to our second two indicators which have to do with the quality of our releases, and how quickly we can recover from failure. If the site is down or degraded, it doesn’t matter how compelling our product is, because we cannot realize returns on our investment if no one can buy the product.

Being able to walk the tightrope between running lots of experiments and the site being very stable is a tension in software delivery. One example of a company that is doing this well is Google. Google is famous in the industry for having “error budgets” which encourage their products to have a minimum amount of “downtime” every month. That means that they want their teams to push as hard as possible to get new code into production (and run those experiments) up until the point where the budget is exhausted and then deployments are slowed or stopped. One must be very good at delivering software to do that safely and effectively.

But DevOps is not just for Development and Operations. It’s for other teams as well, as every team is part of the value stream in some way. That includes security, design, legal, and marketing. I once worked with a marketing team that would only start on collateral (tweets, blog posts, etc.) after a feature was released. We had inventory that we’d paid for and released that was available for weeks that no customers knew about. We revamped our process so that the collateral was released on the same day as the feature so that the investment that was made as a business could be realized with customers engaging with new features weeks earlier than before which led to shorter feedback cycles, greater customer satisfaction, increased revenue, etc.

This was possible because we had a culture of participation and information sharing that let those who were closest to the information decide the best way to execute on the company’s goals. Those in management explained the goals and targets, and left it to the smart, empowered, humans to participate and deliver the results necessary to achieve those objectives. In the DevOps movement, we refer to this as Westrum Generative culture after Dr. Ron Westrum, who proposed the model. Many investors intuitively know that this culture is a key indicator of high growth teams.

Looking forward

It’s clear that at this turning point in the age of software, companies that are able to master the dominant paradigm of the moment will be the ones that survive and thrive in the new “golden age” as described by Dr. Perez. Today, it’s not enough to be big, or loaded with capital. It comes down to execution and speed. To do so, we are going to need to place an emphasis on getting good at delivering software.

If we follow the DevOps model, this can be accomplished in a way that is good for business and our employees, which was the reason behind the formation of Mangoteque. Working employees like cogs in a machine, without respect and consideration, will never compare with the results we can achieve for our companies if everyone is focused on delivering value together to our customers.

Adrian Cockroft, the architect of the Netflix move from data center to cloud, famously tells a story about C-level executives. After giving a talk about the amazing results that Netflix was able to achieve in their engineering organization and for the business he would often be mobbed by C-suite executives after the talk who would declare “That’s amazing! What results! Where were you able to find those talented people?” To which Adrian would reply:

“We hired them from you and got out of their way.”