M&A are the first two letters in MArgins

When I was an architect in Infrastructure Engineering at Salesforce, they would periodically hold all-hands meetings where everyone in San Francisco would go to the Masonic Auditorium so we could all be in the same room together. At one of these meetings I remember Marc Benioff commenting that he had waited too long to integrate the Heroku acquisition into the larger Salesforce ecosystem. He’s not the only one. The Private Equity Playbook describes 3 levers that PE likes to pull to maximize the return on their investments:

- Growth

- Margins

- M&A

Each can be considered in isolation, but a pattern I see often in portfolio companies, combines M&A into the other two in very specific ways.

Growth

If we want to grow the portco, we can develop products and improve products. If we develop a new product from scratch, it can often take a year to develop a software product to a level where customers show interest. It will be interesting to see if AI changes this.

After that year, we get customers onto the product and to a point where they can be referencable for customers that follow. If this takes another year, we are now 2 years into a 3-5 year investment thesis.

Now we have a year to sell this product before thinking about exit strategies. Not much time. Instead, if we execute an M&A strategy we can have a new product, with referencable customers, and an existing customer customer base on the day the acquisition closes.

A much faster path to growth.

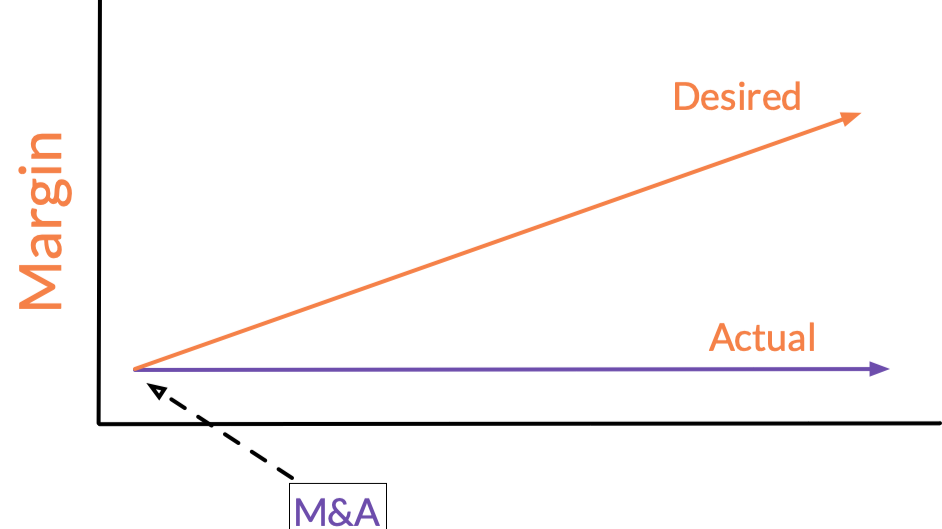

Margins

However, simply acquiring companies is not without its challenges. If you’re a company like Salesforce and acquire a company like Heroku without integrating the two, you now have at least 2 development organizations, 2 security organizations, 2 HR organizations, etc.

But this violates the private equity principle of margins. In order to have high margins we need to have high efficiency, and having multiple functions that all do the same thing is not efficient.

Private equity wants organizations to be high leverage in order to achieve high margins, so people are not continually reinventing the wheel.

47 Lone Wolves

If you’ve read DevOps Patterns for Private Equity you may remember the story of the 47 lone wolves. The company had completed dozens of acquisitions and each time, they would take some of the operations people and put them on a larger team that was dedicated to closing tickets. The more companies that were acquired, the larger the team would get to accommodate the respective larger number of requests that would come in from the combined company.

When a request for service was entered, it could go one of 47 different ways for fulfillment. This meant that people did not have to wait very long to get their requests looked at, which was good.

It also meant that any time work needed to be completed, one of the “wolves” would have to figure out a way to fulfill the request. Unless they had done that specific type of request before, they would have to figure it out anew. In essence, the wheel was constantly being reinvented time and time again as people would try and close tickets.

Definitely not high leverage, and as a result, not high margin as well.

Solution: I worked with the engineers and leadership to understand what types of work was being done by the 47 lone wolves. We then organized the wolves into teams that were responsible for areas of ownership. If a request came in of type A, it would get routed to the team responsible for type A.

Because that team had ownership over that area, they collectively developed tools, processes, and procedures to satisfy those types of requests with the eventual goal of making those requests as self-service as possible.

A much higher-leverage outcome than continually re-inventing the wheel.

5 Compute teams

At another portfolio company, much like Heroku, the acquisitions were not integrated into the R&D organization. Though there were similar products, each acquisition retained their own unique ways of doing things.

Some used modern development tools and deployed on Kubernetes, while others used legacy technologies and were deployed mostly in data centers or on-premises. Even the products which were deployed on Kubernetes could be on vastly different types of installations.

By one architect’s estimate, there were at least 5 different groups that were offering compute resources to their specific area of the organization. What were the chances that there was nothing that could be shared or re-used across the different products, especially those that used the same types of compute resources? Almost zero.

Solution: We talked about the fact that private equity wants high-leverage in order to achieve high margins. Work was being duplicated instead of leveraged. We began to reorganize the various compute teams to leverage the work that had already been done, and build a platform that could be used widely across the organization regardless of deployment model or technology…

Aiming for Exit

…which brings us back to the intersection of M&A, Growth, and Margins. Smart M&A isn’t just about acquiring new revenue streams; it’s about strategically integrating these acquisitions to accelerate growth while creating efficiency and maximizing leverage in order to expand margins.

The 47 Lone Wolves and the 5 Compute Teams were acquisitions, like Heroku, that waited too long to be integrated and thus created duplicated efforts and stunted margins in the process. By integrating early, and aiming for leverage, we can create systems that ensure that M&A truly contributes to both top-line growth and bottom-line profitability, turning acquisitions into well-incorporated parts of a greater whole.